Research

My research focuses on understanding gravitational N-body dynamics and its astrophysical consequences. I have mostly focused planetary systems and have explored a range of topics, from measuring planet masses and orbits via dynamical modeling to understanding the long-term evolution of planets’ orbits. My past research topics have included:

- Scattered Disk Dynamics

- Intra-system uniformity

- Numerical Methods

- Migration and Resonance Capture

- Instability of Mercury

- Dynamical chaos

- Mean motion resonance

- Planet 9

- Transit Timing Variations

Scattered Disk Dynamics

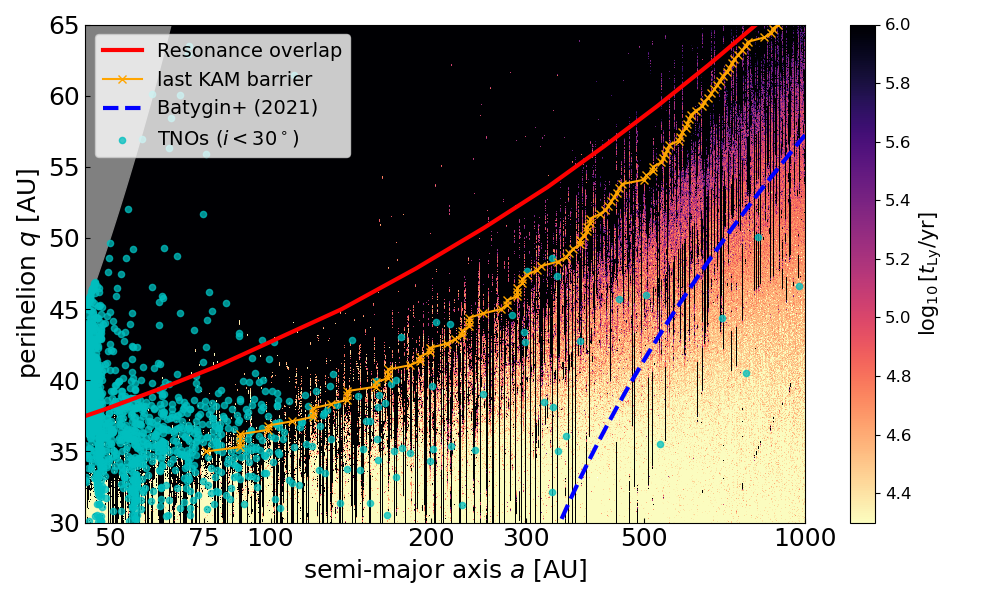

Small bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune are understood to be the remnants of an intially much larger planetesimal population that was dynamically sculpted away by interactions with the giant planets early in the solar system’s history. The scattered disk is a large sub-population of these trans-Neptunian objects whose highly eccentric orbits evolve quasi-randomly due to dynamical interactions with Neptune. With an eye towards better understanding what the orbital distribution of the trans-Neptunian objects we see observe implies about the solar system’s formation and early evolution, I worked out a mapping description of highly eccentric orbits subject to perturbations by a planetary-mass companion in paper with Scott Tremaine. This mapping description elucidates how the orbital dynamics depend pericenter distance and pertuber mass and serves as basis for deriving a statistical description of the chaotic transport experienced by this population over billions of years of dynamical evolution.

Intra system uniformity

A number of observational lines of evidence, including planet masses measured by transit timing variations, indicate that the individual members of systems of multiple sub-Neptune sized planets tend to be more similar to one another in terms of their masses and radii than planets drawn at random from the overall population of sub-Neptunes. In a paper led by University of Toronto undergraduate student Caleb Lammers, we demonstrate that the observed “peas-in-a-pod” trend can be naturally explained as the result of planetary systems undergoing a giant impact phases. We show that instabilities leading to mergers tend to erase any initial dispersion in planet masses and produce systems of planets with similar masses.

Numerical Methods

I developed the open-source Python package, celmech, in collaboration with Dan Tamayo. This package is designed for conducting all sorts of planetary dynamics calculations. By making use of computer algebra capabilites offered by the sympy library, it allows users to apply techniques from dynamical systems and classical perturbation theory to models derived from arbitrarily complex disturbing function expansions. The code is designed to interface directly with the popular REBOUND N-body code.

The code can be installed via PyPI with a simple pip install celmech or by cloning the latest version on GitHub. You can also watch Dan and I discuss the code:

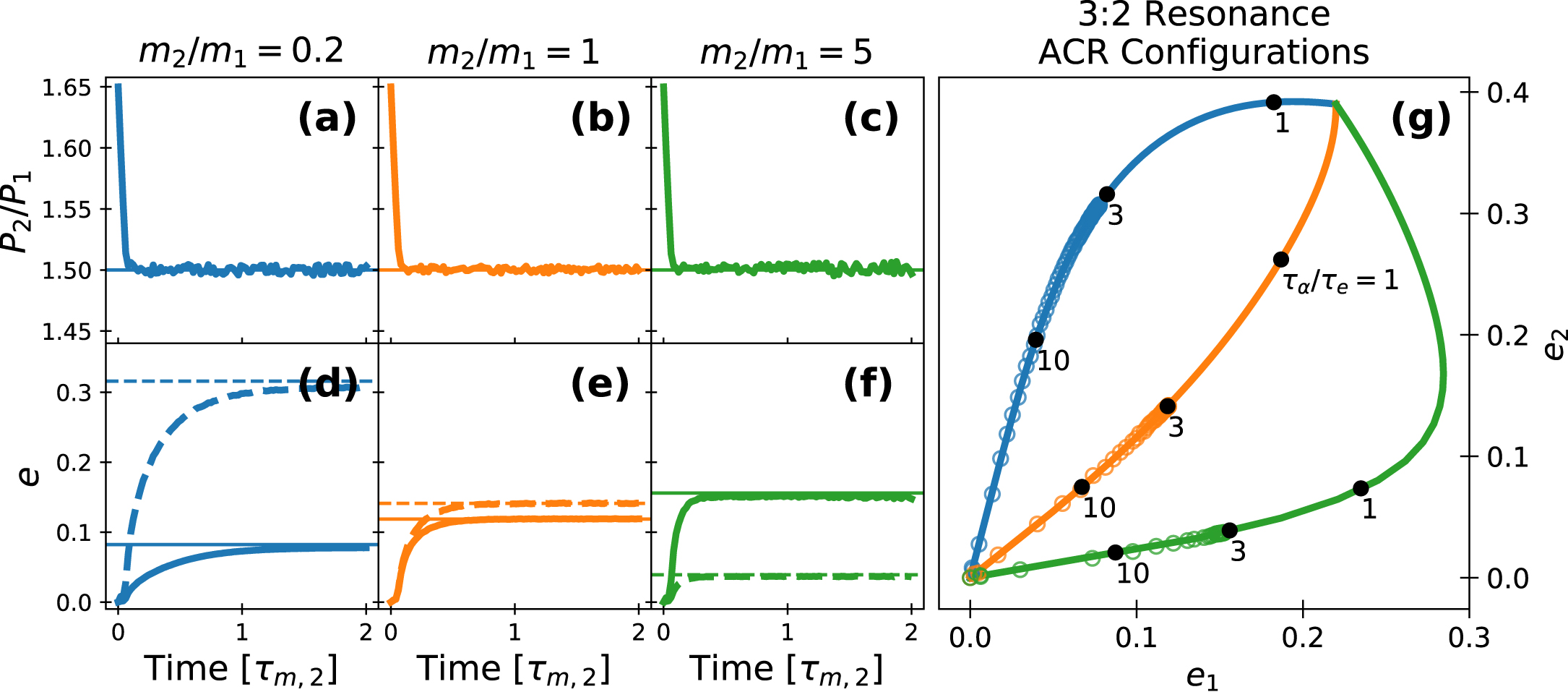

Migration and Resonance Capture

Planets residing in mean motion resonances are generally assumed to reach these orbital configurations as a result of orbital migration and eccentricity damping experienced during the protoplanetary disk phase of a planetary system’s life. In Hadden & Payne (2020) I showed how the dynamical state of resonant planets measured from RV fits could be used to constrain the migration histories that led to MMR capture.

Instability of Mercury

One of the most significant results of modern celestial mechanics is the discovery that Mercury’s orbit is chaotic and potentially unstable. The fact of that the soalr system is chaotic was first established by some landmark N-body simulations starting starting in the late 80s/early 90s. Eventually, it was established that Mercury has a ~1% probability of colliding with the Sun or another terrestrial planet in the next ~5Gyr, approximately the remainder of the Sun’s main sequence lifetime. I’ve worked with collaborators on a series of papers that explore just how early Mercury can be destabilized and how its probability of instability evolves with time ( Abbot et. al. 2021, 2023a, 2023b, Hernandez et. al. 2022)

Dynamical Chaos

In Hadden & Lithwick (2018) I derived an anlytic criterion for the onset of chaos in two-planet systems. This criterion is applicable to the case closely-spaced planets with non-zero eccentricities, the dynamical regime occupied most observed exoplanetary systems.

Mean Motion Resonances

Mean motion resonances (MMRs), integer ratio relationships between the orbital periods of planets or satellites, occur an a wide variety of contexts in orbital dynamics. In Hadden (2019), I derived an analytic model that can accurately capture the resoant dynamics of pairs of planetary-mass objects in MMR.

Dynamics of Planet 9

Batygin & Brown (2016) hypothesized the existence of yet-undiscovered Neptune-sized planet on a distant, eccentric and inclined orbit in order to explain some unexpected clustering in the orbital properties of the most distant trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). In Hadden et. al. 2018, I explored the dynamical mechanisms at play in generating orbital clustering and driving chaotic semi-major axis evolution of TNOs under the influence of Planet 9.

Transit Timing Variations

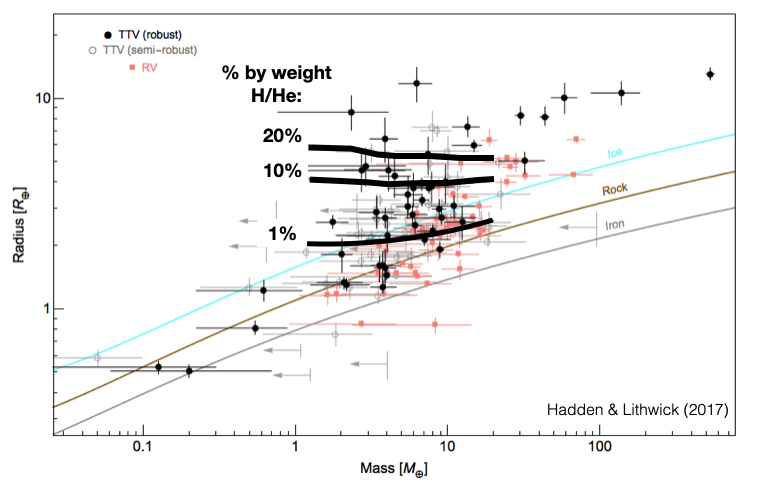

When multiple planets orbit the same star, their mutual gravitational interactions cause their orbits to deviate from perfect Keplerian ellipses. These deviation can be detected in the arrival times of the planets’ transits, which will not be perfectly evenly spaced. While these transit timing variations or ‘TTVs’ can provide exquisitely sensitive probes of small planets masses and eccentricities, going from a set of TTVs to measurements of planet masses and orbits poses a difficult inverse problem.

During my PhD, I worked extensively on developing and applying methods for measuring the masses and eccentricitites of transiting planets using TTVs. This work culminated in an analysis of the TTVs of 145 transiting planets in 55 Kepler systems (Hadden & Lithwick (2017)). This work has helped inform our understanding of the mass-radius relationship for sub-Neptune planets which, as the plot below illustrates, are frequently covered with significant gaseous envelopes constituting up to ~10% of their total mass. The full MCMC posteriors from this work can be downloaded here.

I’ve also developed the ttv2fast2furious code, a suite of python tools for fitting TTV observations.